Naomi Jeffery Petersen, Ed.D. and Rebecca L. Pearson, Ph.D., Central Washington University

Abstract

Individuals use images to make sense of personal and societal situations. We draw and paint to understand and emerge from mental health issues, post photographs on social media to show intimacy with family and friends, create pictorial documents such as infographics to collapse and translate study data into eye-catching, understandable products, and map such population health indicators as infectious disease rates and community experiences with violence so that we can more readily compare and prioritize issues and groups. Many of these actions are best viewed as fitting one category: more useful for individuals or society. One practical qualitative research method, PhotoVoice, spans these categories, allowing people first to view and frame a situation for themselves and then for others. In PhotoVoice projects participants are co-researchers documenting situations, choices, or contexts by taking photos, describing them in writing, and sharing this documentation with others. PhotoVoice is a flexible tool for visual/imagery-based research. Goals typically include helping communities document strengths and risks, promoting dialogue and awareness, and influencing policy change. In this paper we describe a PhotoVoice project in an undergraduate Consumer Health course and include guidelines and examples. Although our focus is on the use of images and associated narratives to understand, describe, and argue for change in population health and social issues, K-12 educators, grass-roots activists, and heritage professionals may also find relevance.

Introduction

“…all sorrows can be borne if you put them into a story or tell a story about them.” Karen Blixen/Isak Dinesen in The Human Condition. (Arendt,1958)

We tell stories to understand and bear our pain, both personal and public, and we value images to help tell those stories. From a parent making shadow puppets while talking a child to sleep to a film with sophisticated cinematography, pictures help us to tell our tales, whether of entertainment, woe, or documentation. Storytelling helps us as individuals and as a society to find meaning. This article focuses on a visual approach to telling stories of communities and why this process is beneficial to all concerned.

Visualizing Ourselves Meaningfully

Humans have always used images to understand, depict, and change their worlds, both internal and external. Very young children take obvious interest in pictures of animals, vehicles, and people – content that matches their own typical experience of a gradually broadening environment. Friends, lovers, and family members pore over photographs that refresh memories, demonstrate commitment, and provide evidence of intimacy. People of all ages immerse themselves in art to enjoy, to understand, to experience awe and reverence.

Individuals draw and paint to express and relieve feelings and mental states (Raggl & Schwartz, 2004). Social scientists translate quantitative data into user-friendly graphs, charts, maps, and,more recently,infographics, an approach that couples easily understood pictures with numbers, percentages, and other evidence to help others understand important findings from scientific reports (Abilock & Williams, 2014).

Viewing images is an obvious way to use them; making and arranging images results in a product usable by others, but the process alone may also be useful for the person creating the product. One example is seen in the use of art therapy, both for children and adults. Both artist and therapist find value in images created as part of art therapy, and literacy surrounding images created is essential for the therapist (Curtis, 2011).

A more general application can be seen in Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences (1983) which posits that there are multiple dimensions for finding meaning, for instance visual and auditory in addition to verbal and logical. This has inspired a generation of teachers to include ‘multiple modalities’ to engage students. This is consistent with learner-centered theories, also called ‘constructivist’, which maintain that delivery of information is not equivalent to learning as the student must make sense of the new information and incorporate it into an existing knowledge base. Piaget’s concepts of assimilation and accommodation address the adjustment made either to one’s understanding of the new information or one’s integration of it into a world view.

One of the multiple intelligences claimed by Gardner is that of a ‘naturalist’. While this assumes a propensity to understand nature, it further assumes an understanding of systems. This understanding is often manifested in metaphors that identify a relationship in one context that could be recognized in another. Nearly all metaphors are visual, that is, physical representations of dynamic functions. Graphic organizers (Ausubel, 1978) reduce the relationships to skeletal figures that allow a more global grasp of the interdependence of elements. Thus the use of such devices as graphics and diagrams is very consistent with the wisdom of systems theories (Deutsch, 1949)

It is noteworthy that one of the benchmarks of science literacy is to know that building models makes it possible to study something that one cannot experience directly (Rutherford, 1993). The collection of information about a focused subject results in a model of that subject and provides the opportunity for the investigator to see patterns and discover details not easily discerned in the immediacy of experience. Science is, of course, associated with testing hypotheses and gathering empirical evidence in a rigorous way that others can replicate. However, the very act of posing a question and designing a way to test it is itself an important pedagogical model. We learn more if we are curious to learn, and the skill of phrasing a question and designing a study is crucial to organizing the information we gather. Thus, however that information is gathered, the process of investigation is valuable for maximum engagement in the process of learning. Inquiry learning is not a replacement for direct instruction of basic procedures and definitions, but it is unquestionably effective in helping students understand complex concepts in complex contexts.

Finally, there is merit in learning new skills in the process of investigation. In addition to gathering data, such as photos, the novice investigator learns the technology of the camera: how to frame, how to focus, how to follow through, and how to finish. This increases competency and autonomy and therefore self-regulation and confidence (Bandera, 1997). When a person in marginalized circumstances experiences the achievement of a project that is shared and found meaningful, there is personal growth that supports further development.

Visualizing Society Meaningfully

Social scientists use images to depict and explain social issues, as well as to argue for change, and suggest how to create that change. Examples can be found in the realm of public health, both in the more activist context of those perceived to be working “politically” to eliminate unjust and socially determined health disparities and in the more mainstream approaches undertaken by those seeking to improve individuals’ health behaviour through theory-based interventions.

Visualizing Health Disparity

Jones developed a graphical depiction of a “cliff” analogy to illustrate how inequitable contexts create health disparities – and in turn how the unjust contexts arise (Jones, Jones, Perry, Barclay, & Jones, 2009). She presented two cliffs, similar in size and shape, but with several differences: people closer to or further from the edge; a fence at the edge or not; safety net or not; ambulance at the bottom or not. In discussing her image (Figure 1), Jones emphasized the difference between the determinants of health and those of equity. Determinants of health create possibilities for, and restraints on, health and healthy decision-making, while determinants of equity create the societal structures and situations surrounding, supporting, and limiting people’s health and decision-making.

Figure 1. Graphic depiction of a “cliff” analogy to illustrate how inequitable contexts create health disparities (Jones, Jones, Perry, Barclay, & Jones, 2009).

Jones’ graphic is simple and unembellished, crafted of heavy, wavering lines and stick figures. Given that her intention was to explain unjust differences in children’s outcomes, specifically, this style likely reflects a purposeful choice. The language she used to explain her image, and make her case for its use in public health efforts, is likewise straightforward: Having discussed the idea of the levels of prevention and how components of her analogy depict them, she stated:

Together, policymakers and community leaders could decide, for example, that it is important to have an ambulance on call and build a strong fence, but that most health resources should be devoted to moving the community away from the edge of the cliff. (Jones et al, 2009, p. 4)

The Social Ecology Model

Another image, a set of concentric circles depicting a common interpretation of McLeroy’s Social Ecology model (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988), is less provocative than Jones’ cliff analogy. Rather than comparing an advantaged population of stick people to a less advantaged one, this diagram describes the context public health practitioners view as surrounding all people’s health outcomes.

Sharing Jones’ image likely engenders a conversation – one that may be more or less confrontational depending on the audience. The Social Ecology model in contrast is more specifically useful, perhaps, for researchers and other professionals wishing to investigate, describe, explain, or plan strategies designed to make measurable change in any of the levels of the context. This second image points out that public health and other social services practitioners can choose to address factors at any of several levels: knowledge, skills, and beliefs of individuals; norms, values, and behaviors exhibited by peers and family; support provided by community organizations; policies in workplaces, schools, and agencies; and societal ideologies that surround law and policymaking.

The Social Ecology model and other diagrams illustrating behavioral and other theory in public health suggest ways to intervene in issues and are used as a foundation for building, and testing, strategies designed to improve population health status. Collected data provide evidence that change is needed; images make the case that we must, and can, collectively make efforts to change.

As noted above, graphs, charts, maps, and now infographics help social scientists share information about societal situations, differential health and social outcomes, and hypothesized reasons these situations and outcomes exist. In all these cases, graphics and imagery can be seen as telling the story of a given issue. Like shadow puppets or film imagery, they help us to see scenes and discern patterns in a way that would be difficult if not impossible using text or oral narrative alone.

Common Visualization Tools

Social scientists, and those who translate research findings in the classroom, the conference room, the media, and the community rely on viewer-friendly images to share messages arising from data. Typically a researcher or other professional has created the image-based tools designed to help audiences understand gender, race, regional and other differences in disease and other experiences.

These tools, then, are often the products, and possessions, of those with specialized academic backgrounds rather than of community members. However, a method exists to help bridge the divide between scientist and community, to help the general public get involved in the production of data-based information surrounding issues of importance to them. A research methodology in which participants take and interpret photos of life situations, contexts, constraints, and decisions, PhotoVoice aids people in telling their stories. Far beyond helping individuals to “bear sorrows,” the goal of PhotoVoice is to empower individuals and groups to help make social change. This tool gives literal voice to real – and personally relevant – images produced, owned, and shared by those whose lives they depict.

Using PhotoVoice for Communities as Co-Researchers

PhotoVoice is a unique, practical, and flexible tool that can be used by groups who are curious about their communities (e.g. Aslam et al. 2013). Participating in a PhotoVoice project offers a chance for individuals to make sense of their own contexts and situations, and usually projects include an opportunity to share the sense making with others. Goals typically include helping communities document strengths and risks (e.g. Baquero et al, 2014), promoting dialogue and awareness (e.g. Hall & Bowen, 2015), and influencing policy change (Slimming, Orellana & Maynas, 2014).

Researchers who employ PhotoVoice to investigate issues are well aware that those who take and explain the photographs are the true researchers, with the investigator planning the study serving primarily as a facilitator. It is effective because the visual images are immediate reflections of the reality and they facilitate a common perception of the community as it actually is (Little, Felten & Berry, 2015). Myriad ways of using this method exist, limited only by the extent to which a participant can use a camera and consider meanings of resulting photos. Below we describe settings and rationales for use of PhotoVoice before turning to a description of its application in an undergraduate 200-level Consumer Health course within a Public Health Major.

The tradition of investigative journalism was much enhanced by the introduction of photography and the current digital devices have made all people holding a smart phone into instant documenters (Aubert & Nicey, 2015; Borges-Rey, 2015). PhotoVoice, the technique described here, is not used for instant reporting of one incident but for visual/imagery-based research. There is an official PhotoVoice organization in Great Britain (photovoice.org) whose mission is to “help those who are often the subjects of photographs to become the photographers and tell their own story”. Their emphasis is social justice through charitable organizations (e.g. Mayfield-Johnson, Rachal & Butler, 2014). It is at the simplest end of the spectrum of which can include sophisticated recorded storytelling such as StoryCorps. A variation is Living Voices, a technique of combining background video with an actor impersonating an historic character.

Activism

The balance of power defines the struggle for social justice, for those who are in power do not experience the injustice and are therefore resistant to change. The radical and revolutionary are frustrated by the deaf ears turned to their theoretical and empirical arguments. As with all effective teaching, they must find a way to make the injustice obvious. This clarification is best if the framed scene appears self-evident, so the observer can feel as if the truth has been discovered based on reality. PhotoVoice presents the reality in the most authentic way: without artifice, without posing, without influence. Photojournalism, once a novelty, is now the norm, especially via mass media. Recently, the casual citizen’s use of smartphone technology to record and instantly broadcast interactions has established a level of accountability that certainly undermines traditional abuse of authority. PhotoVoice is a much more thoughtful and deliberate effort than an ambush snapshot that may be out of context, producing a product that can be used for reference.

Heritage

Everyday events are rarely recorded, even in diaries, hence the keen interest in historic journals such as Samuel Pepys’ and Anne Frank’s. A tradition or event so recorded becomes so honoured, and thus a culture’s heritage is reflected in the records of its expression. Marginalized populations are no less rich in heritage but impoverished in terms of documentation. Marginalized populations are also more likely to be impoverished materially, with limited access to the technology necessary for recording as well as with limited time to conduct the investigation. PhotoVoice facilitates the orientation to the procedures necessary to accomplish the primary goal: document realities of interest.

Education

Zenkov and Harmon noted that evidence exists to support the use of PhotoVoice and similar data collection methods in education: There are insights those exploring education issues will not be able to make without picture-based inquiry because the data are simply “not available via language-centered procedures” (2009, p. 576).

This is therefore a promising tool for groups that include English Language Learners and others who may be at risk of exclusion or misunderstanding. The current standards of best practice in the classroom caution teachers to provide multiple modalities in which students can learn and also demonstrate their learning. If a concept is worth learning, it should be meaningful to anyone, and using PhotoVoice in the classroom may allow students to find – and produce and express – meaning when they otherwise might not.

PhotoVoice in an Undergraduate Consumer Health Course

Discussing the need to change society, let alone the possibility of such change, is difficult in the classroom as well as in other settings and can lead to the accusation that an educator or other person is being impartial, or even political. A logical response to, or pre-emption of, such a claim is to make the change imperative and opportunities self-evident, to “hold up a mirror” to those experiencing an issue.

To ask people to reflect critically on an image they record from their own reality is in effect to challenge them to hold the mirror, allowing PhotoVoice participants to show themselves – and others – what must and, potentially, could change. This challenge may be especially effective in the undergraduate consumer health classroom.

Curriculum Context

For several years one of the authors has taught a ten-week lower division consumer health course designed to meet the needs of public health majors as well as students seeking elective credit; the course has recently been made part of our university’s general education offerings. The instructor opens the course by explaining alternative societal paradigms, such as market justice and social justice. This opening sets the stage for students to decide for themselves that consumer health issues are likely socially constructed and situated rather than merely reflections of individuals’ differing levels of health-related awareness, skill, or commitment. Following this introduction and contextualizing, the course takes a “pre-conception-to-grave” approach. Students read about, reflect on, discuss, and participate in lectures focused on information about health and social issues – and personal and societal options for improvement.

The PhotoVoice Project

Approximately halfway through the course, the PhotoVoice project is introduced. Students may choose to work alone or in pairs, and the instructor emphasizes:

- The importance of accuracy (rather than manipulation) in documenting their reality through images,

- Safety when obtaining photos, and

- Omitting, or ensuring anonymity of, actual persons in photographs.

In addition to these basics, students are informed that they can take the project in one of a couple of directions: They may look for photo opportunities in an attempt to answer a research question such as “How healthy are the available options?” Alternatively students may elect to take photos first, perhaps of three separate purchases or money spending opportunities, and then determine – and write about – for example, what the images have to “say” about their own current and likely long-term health or about the possibilities the general consumer has for making healthy decisions in the same realm.

Finally students are ask to write about their experiences of collecting image-based data, about how useful PhotoVoice would be for other individuals wishing to improve their own health, and about how they can see using it in their work as future public health professionals or in other work or community settings. See Appendix for a recent version of student-friendly and community-friendly guidelines.

Student Response to the PhotoVoice Project

Although the wide-open nature of the assignment results in some students feeling (and verbalizing) stress, once questions are raised and answered all students typically state that they are confident they can successfully complete the project. Furthermore, most students then express that they are excited about getting started. [R11] Many view the assignment as an unprecedented, and intriguing, challenge. They recognize that, in a sense, they will be designing their own learning opportunity and subsequently sharing the resulting learning.

Given that the project is introduced mid-quarter, following the first sessions in which consumer issues surrounding food and diet-related health have been discussed, many students choose to “picture” their food environments or typical choices. Over-the-counter medications, diet aids, and supplements are also commonly addressed. Less common photograph subjects include clothing, commercial exercise facilities, signage and buildings in various areas of town, and bike racks and other structural components that support or inhibit active transport. An unusual choice was made by a student who saw different state laws surrounding snake ownership as impacting consumer awareness of their options for choosing an interesting and easily maintained pet; after receiving the instructor’s permission to record existing images, rather than actual things, he chose to take photographs of agency websites and language he perceived as impactful.

Examples of Student PhotoVoice Project Excerpts

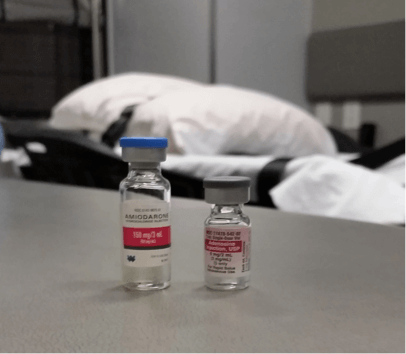

Below are example images and the accompanying brief narrative from student submissions. The first four images (Figures 2-5) are perhaps obvious in their intent, especially with the accompanying narratives. The fifth image (Figure 6) and narrative were produced by a student who observed her own workday as an EMT; she discussed the direct connection she saw between economic factors and health-impacting decisions, especially those made by others based on policy.

Figure 2. Photo of fast food alley by a Junior Public Health Major. “I stood in the Baskin-Robbins parking lot to this picture. The aspect that stands out to me the most is the fact that these fast food signs are so visible from very far away which makes it very convenient. This makes it difficult to make healthy choices when in our society convenience is king.”

Figure 3. Photo of produce bag by a Sophomore Honors College Student. “Local doesn’t mean healthy or good for a person’s health. Being an American consumer means that we have access to the world market which means we have options and can make choices. Look both in your community and beyond to find your personal healthy.”

Figure 4. Photo of bike sticker by a Sophomore Honors College Student. “This is a project started by local bike enthusiasts who wanted to take a stand to thieves. This shows that the consumer does have power even though consumers are often told that do not. This project gives the power back to the consumer.”

Figure 5. Photo of storage units by a Senior Nutrition Major/Public Health Minor. “I love the idea of this picture because it seems counter intuitive. The idea is that we store our unused items in a storage unit for when we might use them again. But when does this idea start snowballing into a bigger issue? One of these units was mine when I was in the process of moving. With that being said, the question that I think relates the best to this picture is how healthy is it?”

Figure 6. Photo of medicine by a Senior Public Health Major & EMT Tech.”What choice do I have? In that situation best practice is followed, meaning you will receive this expensive medicine vs. the inexpensive medicine.”

Finally the sixth image (Figure 7) and narrative are those of the student described above, showing the link between policy change and options available to consumers who enjoy keeping reptiles as pets.

Figure 7. Press release used as part of PhotoVoice project by a Sophomore Biology Major. “They did it. The USARK managed to get the recent Lacey Act add-ons revoked. Due to community support and some hard work and effort by their team they managed to undo this travesty and put control of our snakes back into the hands of the US citizens so no person who is forced to move for any reason no longer has to give up, kill, or release their snakes. We as responsible reptile owners have the upper hand again.”

Student Reflections on the PhotoVoice Experience

The narrative students produce in response to the additional prompts is often valuable both from a pedagogical perspective and a consumer health improvement perspective. In discussing the process of closely viewing the depicted products while taking her photos, one student wrote:

While taking my photos, I was fascinated with the pros and cons of using supplements and/or replacements, and how the average American could understand this importance. Taking this class enabled me to observe from a different perspective. For example, one thing that stuck out to me was the use of isolates.

Although student enthusiasm and “a ha” moments and connections to course content are not always as clear in the writing itself, the additional opportunity to present to fellow students consistently elicits such expression from both the photographer and the audience. In fact, the visual literacy aspect of the work emerges clearly in the students’ presentations. Frequently, even before a student speaks, other students and the instructor are smiling, laughing, groaning, expressing shock, or rolling their eyes at an image. The presenting student may respond with “See? I kid you not; that’s what we’re dealing with when it comes to healthy food in this town” or a similar remark that shows the audience “got” exactly what was intended.

Student Outcomes from the PhotoVoice Project

An important aspect of all learning, of course, is that students master technical skills if applicable, and concern themselves with quality as well as with completion. In keeping with the visual literacy connection, one resource provided by PhotoVoice.org to help photographers capture quality photos is an infographic titled “The Four Fs.” The class in which the described PhotoVoice takes place is not a photography class, and students generally have the capacity to take adequate photos with their cell phones or other devices; thus, to date the instructor has not emphasized technical skill or details to take “good” photos. The emphasis in this class is on the meaning, and the interpretability, of the images they capture. A few students put strong personal emphasis on taking collecting high-quality pictorial data – and some apologize during presentations if they feel their photos are not as excellent technically as they had hoped.

As previously stated, this level of production detail is not a focus of the project in the described class. On the other hand, quality work is expected and most students do produce that: They take several photos that typically do exemplify an attempt to capture a personally meaningful and health-relevant image; they explain details of their thought processes in writing and in presenting; they attempt to bridge gaps between what they intended to capture and what their audience, their classmates and the instructor, may see. Other instructors may wish to focus more on technical aspects of picture taking, and the “Four Fs” resource may well be used in future versions of the described class. Beyond helping students who wish to concentrate on producing high quality images, it has the potential to raise the level of quality of all the students’ work without much consternation on their end: In effect, it will add a visual literacy support to their understanding of the assignment expectations and purpose.

Recommendations for Further PhotoVoice Project Design

The described use of PhotoVoice is highly adaptable, based on both educational level and course content. Considering PhotoVoice in this way as a teaching tool also allows instructors to modify guidelines in any way they see fit. During the most recent session of the consumer health course, the instructor added an option for students to create short videos instead of simply taking photographs. Although no students pursued this option, several expressed interest but felt their skills too limited. It might be valuable, and practical, for an interested instructor to support students in producing short videos as part of a “voice” project similar in nature to this one but using moving images instead of stills.

References

Abilock, D., & Williams, C. (2014). Recipe for an Infographic. Knowledge Quest, 43(2), 46-55.

Aslam, A., Boots, R., Link, S., Pearson-Beck, M., Mayton, H., & Elzey, D. (2013). Effective community listening: A case study on PhotoVoice in rural Nicaragua. International Journal for Service Learning in Engineering, 8(1), 36-47.

Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition. University of Chicago Press.

Aubert, A., & Nicey, J. (2015). Citizen photojournalists and their professionalizing logics. Digital Journalism, 3(4), 552-570.

Ausubel, D.P. (1960). The use of advance organizers in the learning and retention of meaningful verbal material. Journal of Educational Psychology, 51, 267-272.

Bandera, A. (1999). Self-efficacy: The exercise of self-control. W.H. Freeman.

Baquero, B., Goldman, S. N., Simán, F., Muqueeth, S., Eng, E., & Rhodes, S. D. (2014). Mi cuerpo, nuestro responsabilidad: Using PhotoVoice to describe the assets and barriers to sexual and reproductive health among Latinos. Journal of Health Disparities Research & Practice, 7(1), 65-83.

Borges-Rey, E. (2015). News images on Instagram. Digital Journalism, 3(4), 571-593.

Curtis, E.K.M. (2011). Understanding client imagery in art therapy. Journal of Clinical Art Therapy, 1(1), 9-15. Retrieved September 3, 2015 from http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=jcat

Deutsch, M. (1949). A theory of cooperation and competition. Human Relations 2: 129–152.

Hall, P. D., & Bowen, G. A. (2015). The use of PhotoVoice for exploring students’ perspectives on themselves and others. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 9(3), 196-208.

Jones, C.P., Jones, C.Y., Perry, G.S., Barclay, G. & Jones, C.A. (2009). Addressing the social determinants of children’s health: A cliff analogy. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 20(4), 1-12.

Little, D., Felten, Peter, & Berry, Chad. (2015). Looking and learning: Visual literacy across the disciplines. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, no. 141).

Mayfield-Johnson, S., Rachal, J. R., & Butler, J. (2014). “When we learn better, we do better”: Describing changes in empowerment through PhotoVoice among community health advisors in a breast and cervical cancer health promotion program in Mississippi and Alabama. Adult Education Quarterly, 64(2), 91-109. doi:10.1177/0741713614521862

McLeroy, K.R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Qarterly, 15(4), 351-377.

Raggl, A., & Schratz, M. (2004). Using visuals to release pupil’s voices: Emotional pathways to enhancing thinking and reflecting on learning. In Pole, C. (Ed.), Seeing is believing? Approaches to visual research,Vol. 7, 147–162. New York: Elsevier.

Rutherford, J. (1993). Benchmarks of Science Literacy: Project 2061. American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Slimming, P. T., Orellana, E. R., & Maynas, J. S. (2014). A PhotoVoice study in the Peruvian Amazon. Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 10(2), 123-133.

Zenkov, K., & Harmon, A. (2009). Picturing a writing process: PhotoVoice and teaching writing to urban youth. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 52(7), 575-584. doi:10.1598/JAAL.52.7.3

Appendix

Health Education 209 – Consumer Health

PhotoVoice/Video Story Project

Our Goal: to have a service-learning experience collecting and analyzing information about consumer health using a unique and powerful methodology, PhotoVoice or Video Story Telling.

Overview: You will be taking photos or creating a short video plus producing brief written pieces to be shared during our final class session as a community forum.

Project Timeline

Week 1: Project Approval. In class, sign up with a brief idea/direction

- Establish partnership (optional) with someone interested in similar topics.

- Choose at least TWO of the following questions to guide your investigation:

- “How healthy IS it?”

- “What choice/s do I have?”

- “Do I really know what I need to to make a healthy choice?”

- “Why is it so difficult to be healthy/easy to be unhealthy?”

- “What’s depletion got to do with it?”

- “Is this not the right kind or layout of information to help me make a good decision?”

- “Who has the upper hand and how?”

- “Who’s selling me what?”

- “What’s the typical discourse (what “most people” say?) about this & similar products/services?”

Weeks 1 & 2: Investigations

- Gather photos or take videos to illustrate your topic in the community.

- Record your thoughts related to the questions you chose to pursue.

Week 3: Documentation

- Submit one (1) Word document to the PhotoVoice Assignment Discussion:

- Photos and captions (OR a separate short video file)

- Approximately two pages (500 words) describing

- Your experience of taking the pictures or creating the video;

- How your consumer health thinking has changed related to the experience;

- Thoughts on how someone who had never been exposed to discussions of consumer health issues and approaches might benefit from seeing this project or doing a similar project.

- Troubleshoot your project and refine its presentation based on feedback and discussion.

Week 4: Presentation

Present a finished project featuring your images and key concepts. Class sessions will devote some time to mastering the tasks.

Rules of Engagement

- Be discreet. Focus on the community: NO FACES of individual PEOPLE in photos or video unless

- ANY identifying info/parts are blurred out; and/or

- You have written permission from the person for unlimited use of the image.

- Be safe. Do NOT put yourself or anyone else at risk in order to get a photo!

- Be creative but accurate and truthful about the subject of the photo

- OK to use PhotoShop software to make colors stand out more, for example, but

- NOT OK to, say, crop out the fine print on a label so it looks like there’s NO info provided)

- Be professional in your work & proofread your write-ups for typos, etc. Remember – your pics and writing COULD result in a more public, “beyond the classroom” dissemination/sharing!

Technical Procedures

To take photos, follow the 4 Fs: Frame it; Focus it; Follow through; and Finish it.

To insert a photo into a word doc:

- Save your .jpg picture with a logical title somewhere you know you can find it (n drive, jump drive, desktop, etc);

- Open the Word document to which you want to add the pictures.

- Click Insert (looks like a paper clip).

- Click Picture (looks like a tiny sketch of a landscape),

- Choose “From File”.

- Browse to locate the picture file, and click Insert.

- Label each picture with what is meaningful about the topic.